When most movie fans hear the words “film noir,” they probably think of movies from the genre’s classic period in the 1940s and ’50s: Humphrey Bogart as a ragged gumshoe in The Maltese Falcon (1941), Barbara Stanwyck’s femme fatale Phyllis Dietrichson descending the stairs in Double Indemnity (1944), or James Cagney on the top of the world in White Heat (1949).

But noir isn’t limited to a single time period, nor is it only about crime stories. Films noir, aka “dark movies,” continue to be made, with noir themes and style filtered through a variety of genres, including science fiction. 1982’s Blade Runner is, of course, the most obvious example of this melding and a mainstay on any film fan’s list, but sci-fi noir goes far beyond Ridley Scott’s classic.

Decoy (1946)

Although the films noir of the classic era tended toward street-level stories with few fantastic elements, some did occasionally borrow sci-fi and horror tropes that were also popular during the time. Dark Passage (1947) staring Humphrey Bogart involves a criminal getting plastic surgery to completely change his face, while Kiss Me Deadly (1955) follows characters chasing a briefcase full of radioactive glowing material (a classic MacGuffin later referenced in films like Repo Man and Pulp Fiction).

Directed by Jack Bernhard, Decoy stands out for its unrelenting violence and Jean Gillie’s standout performance as the murderous Margo Shelby. But sci-fi fans will also note its use of mad scientist technology that brings gangster Frank Olins (Robert Armstrong) back to life after he’s executed by the state. While the mad scientist stuff is a minor element in the story’s overall narrative, it’s worth noting as the first instance of sci-fi noir.

Alphaville (1965)

After Decoy, neo-realist pioneer Jean-Luc Godard more thoroughly blended together science fiction and noir for Alphaville. Godard transports secret agent Lemmy Caution—created in the ’30s by British novelist Peter Cheyney and played by Eddie Constantine in a series of French B-movies—to a dystopian future where a computer called Alpha 60 runs the city of Alphaville. Caution’s gritty style runs contrary to the detached behavior of the Alphaville citizens, who favor logic over emotion.

Ironically, Godard approaches the subject in a manner closer to Alpha 60 than that of his hero Caution. Even when he’s grouching against the human automatons surrounding him, Caution feels disconnected and stilted, thanks in part to Godard’s use of improvised dialogue and hand-held camera shots. Ultimately, Alphaville is an interesting genre exercise that is very aware of the genre trappings it’s combining.

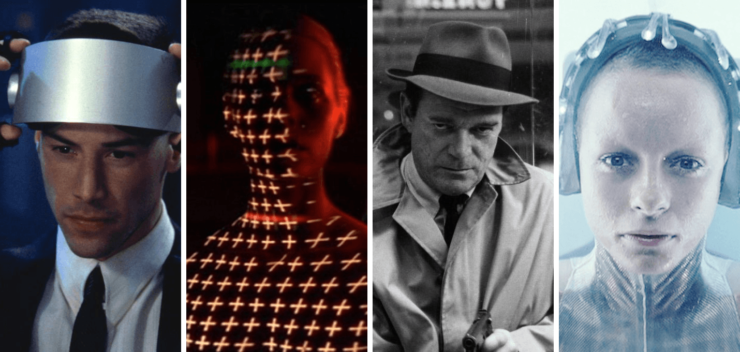

Looker (1981)

After mixing science fiction with westerns for 1973’s Westworld, it’s no surprise that writer/director Michael Crichton would eventually create his own unique take on the film noir. Looker stars Albert Finney as Dr. Larry Roberts, a plastic surgeon who becomes a favorite among supermodels seeking minor, seemingly inconsequential procedures. When these models begin dying, Roberts launches an investigation that draws him into a mystery involving an advertising firm’s plans to digitize and control the models.

Like most of Crichton’s work, Looker is amazingly forward-thinking, predicting the use of the kind of digital representations that only came into prominence in the 2010s. Also in keeping with most of Crichton’s directorial work, Looker often feels inert and its performances flat. But between its exploration of the relationship between society’s beauty standards and technology, along with its Tron-esque visuals, Looker is worth checking out.

Brazil (1985)

With its fantasy sequences involving a winged knight battling a mecha-samurai, Terry Gilliam’s masterpiece Brazil doesn’t seem to have much in common with movies like In a Lonely Place or The Stranger at first glance. But it’s important to remember that noir has always used dreamlike imagery to convey a character’s inner life.

With that in mind, Brazil’s noir bonafides become clearer. Government bureaucrat Sam Lowrey wants nothing more than to keep his head down and to live in comfort in his apartment filled with ostentatious mod cons. A promotion secured by his pushy mother and a visit from a vigilante HVAC repairman push Sam out of his comfort zone, but the real shock to his system comes when he encounters American Jill Layton (Kim Greist), whose resistance against the government both frightens and inspires Sam. The tension between straight-laced Sam and femme fatale Jill drives the movie, even as it spins further into absurdist totalitarian farce.

Johnny Mnemonic (1995)

The ’80s may have given audiences the world’s most famous sci-fi noir in Blade Runner, but the subgenre truly hit its peak in the 1990s. Three of the most notable entries debuted in 1995 alone, starting with the Keanu Reeves vehicle Johnny Mnemonic, directed by Robert Longo. An adaptation of the William Gibson story by the same name, Johnny Mnemonic follows the adventures of Johnny (Reeves), a courier who has transformed his brain into a hard drive in order to carry contraband data. When he’s hired to transport information about a cure for a type of drug addiction paralyzing the lower classes, Johnny must team up with resistance fighters Jane (Dina Meyer) and J-Bone (Ice-T) to fight off assassins working for a totalitarian pharmaceutical company.

Despite that compelling and over-stuffed plot, Johnny Mnemonic never really pops on the screen. Reeves is still years away from developing the world-weariness his character requires, and despite occasional gestures toward unique set design, the world feels strangely underdeveloped. The movie does include a great scene in which Reeves stands atop a pile of garbage and rants about room service, but it never fully lives up to its potential, despite climaxing with a showdown between a Bible-thumping killer played by Dolph Lundgren and a cybernetic dolphin.

The City of Lost Children (1995)

Like Brazil, Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s The City of Lost Children seems to belong primarily to a genre other than noir, namely cyberpunk. The directors fill the story, written by Jeunet and Gilles Adrien, with bizarre imagery, including a cyborg cult, clone siblings, and a mad scientist’s machine that steals dreams. But in addition to a labyrinthine plot that prioritizes sensational events over narrative cohesion, The City of Lost Children features one of the key noir tropes: that of a dejected outsider taking on seemingly unstoppable forces.

That outsider is One, a simple-minded circus strongman played by Ron Perelman, whose participation in a robbery ends with him teaming with the orphan girl Miette (Judith Vittet) to rescue his kidnapped little brother Denree (Joseph Lucien). With a soaring score by Angelo Badalamenti, fantastic costumes designed by Jean-Paul Gaultier, and Caro and Jeunet’s signature visual style, filled with Dutch angles and extreme close-ups, The City of Lost Children can be an overwhelming watch. But it ties into the same surrealism and ragged, indomitable spirit found in the classic films noir.

Strange Days (1995)

Even more than the aforementioned films (along with Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys, which didn’t quite make this list), the best sci-fi noir of 1995 is the hard-to-find Strange Days. Directed by Academy Award winner Kathryn Bigelow and co-written by James Cameron, Strange Days is an intense experience. Playing against type, Ralph Fiennes plays Lenny Nero, a sleazy ex-cop in Los Angeles who deals SQUIDS—minidiscs that record one person’s memories for others to download and experience. After procuring a SQUID that records a robbery that exposed sensitive information, Lenny must team with his former girlfriend Faith Justin (Juliette Lewis), chauffeur/bodyguard Mace Mason (Angela Bassett), and private investigator Max Peltier (Tom Sizemore).

Inspired in part by the riots that occurred in the wake of the LAPD’s beating of unarmed Black man Rodney King, Strange Days is perhaps the most perfect melding of noir attitude and sci-fi technology. Bigelow’s unrelenting approach can make the movie a difficult watch, both in terms of style (she portrays the SQUID recordings as first-person assaults) and substance (including a scene in which Lenny experiences a SQUID capturing a rape from the victim’s perspective). Yet there’s no denying the movie’s power and conviction.

Dark City (1997)

Most ’90s neo-noir keyed into the German Expressionist influence of classic noir, but none replicated the style quite like Dark City. Directed by Alex Proyas, who co-wrote the film with Lem Dobbs and David S. Goyer, Dark City is a striking, moody film that ties extraterrestrials and outlandish technology to a standard noir story about an amnesiac recovering his identity. Rufus Sewell plays John Murdoch, who awakens in a hotel bathroom with no memory just as a phone call from Dr. Schreber (Kiefer Sutherland) urges him to flee the trenchcoated men coming to get him. What follows is a twisty story that goes far beyond crooked politicians and gangsters, all the way to meddling aliens.

Like many of the great films noir, Dark City‘s narrative doesn’t entirely make sense. And as with many of the previous classics, that doesn’t matter. Sewell turns in his best performance as the desperate Murdoch, William Hurt shows up to chew the scenery as a skeptical detective, Sutherland is still in his pre-24 weirdo mode, and Jennifer Connelly excels in the wife/fatale role. Combined with Proyas’ striking visual style, Dark City is an excellent capper to a decade of remarkable sci-fi noir.

Minority Report (2001)

As a director best known for capturing wonder and nostalgic adventure, Steven Spielberg seems like an odd choice for a tech-noir adaptation of a Philip K. Dick story, especially with megastar Tom Cruise in the lead. And yet, Minority Report is a stylish, thoughtful mystery movie wrapped up in an immensely crowd-pleasing package. Cruise plays John Anderton, a member of the PreCrime police, who arrest people who will commit future crimes predicted by a trio of “Precogs.” But when the Precog Agatha (Samantha Morton) predicts that he will murder a man he’s never met, Anderton must go on the run to avoid his fate before he’s captured by investigator Danny Witwer (Colin Farrell) and PreCrime Director Lamar Burgess (Max von Sydow).

Minority Report is an immensely enjoyable movie, with all of its Hollywood players at the top of their game. Spielberg keeps the proceedings sleek and shadowy, creating a compelling world in which Cruise embodies the desperate and determined agent. More importantly, Minority Report taps into questions about security and innocence that would become imperative during the post-9/11 period and continue to challenge us today.

Upgrade (2018)

The directorial debut of Saw co-creator Leigh Whannell, Upgrade is tech-noir with an action-movie twist. Logan Marshall-Green stars as Grey Trace, a mechanic whose life falls apart after an attack by thugs leaves him a paraplegic and his wife (Melanie Vallejo) dead. Trace reluctantly accepts a STEM implant from eccentric inventor Eron Keen (Harrison Gilbertson), expecting only that it will allow him to walk again. But the implant (voiced by Simon Maiden) not only helps Grey identify the men who murdered his wife but also endows him with incredible hand-to-hand fighting skills, which he’ll need as he follows the trail of corruption he uncovers.

The brutal fight scenes, shot with a thrilling inventiveness by Whannell, may be Upgrade‘s primary draw, but they just provide a sugary topping to the film’s satisfying mystery. Marshall-Green plays a perfect noir hero, an unremarkable everyman who is out of his depth against the powers he takes on. Factor in Blumhouse regular Betty Gabriel as the detective trailing behind Grey and his enemies, and the movie becomes as much a taut thriller as it is an explosive action movie. Upgrade proves that noir remains a vibrant genre well into the 21st century—especially when mixed with science fiction.

Originally published November 2020.

Joe George’s writing regularly appears at Bloody Disgusting and Think Christian. He collects his work at joewriteswords.com and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.